When asking the question “who invented zero,” we delve into one of the most transformative ideas in human history. Zero, an abstract concept with profound implications, was not always part of mathematics. Its journey from a placeholder to a number with its own identity reshaped how civilizations understood and interacted with the world. This article explores the origins, evolution, and significance of zero, highlighting its role in ancient cultures and modern sciences.

The Origins of Zero: A Historical Perspective

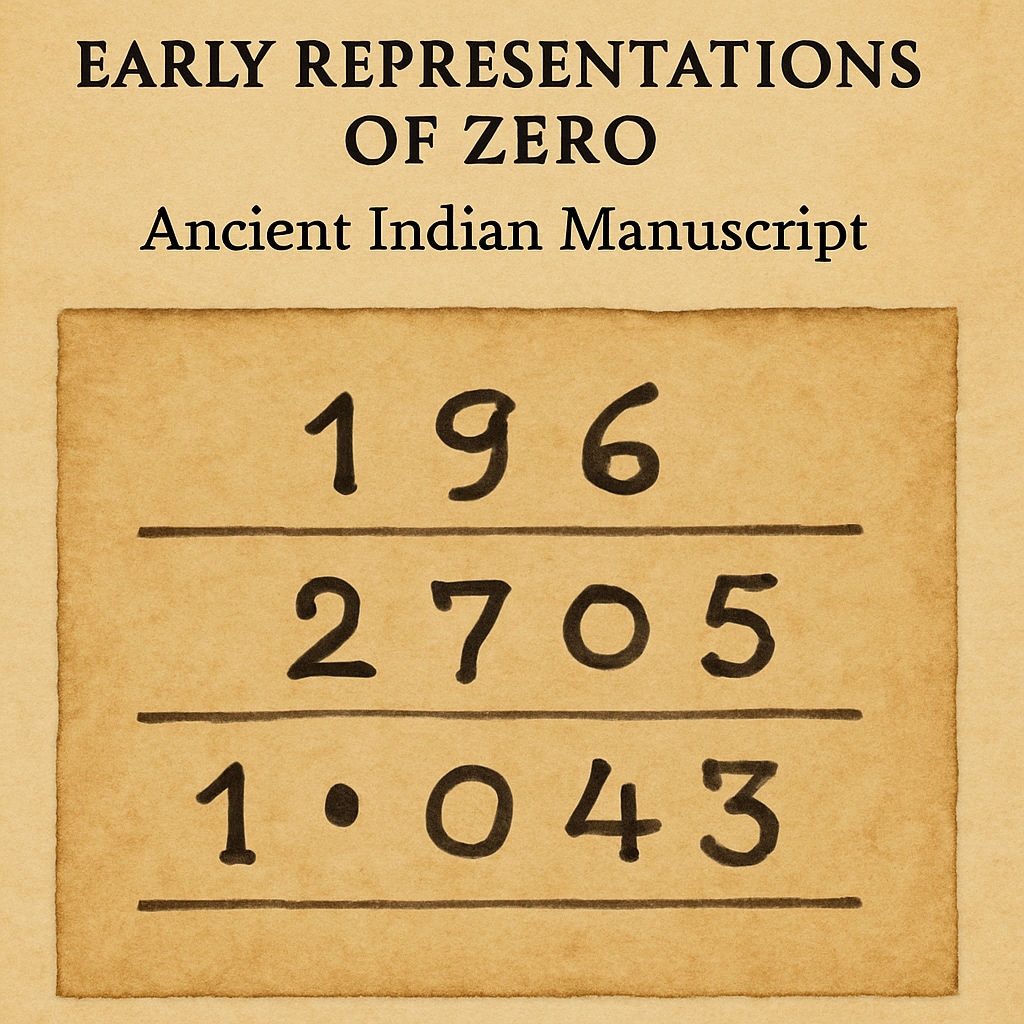

Zero’s story begins in the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, India, and beyond. In Mesopotamia, dating back to around 300 BCE, the Babylonians used a placeholder symbol in their base-60 numeral system. However, this symbol was not considered a true “zero” as we understand it today—it lacked numerical value and philosophical depth.

The breakthrough came in India during the 5th century CE. Indian mathematician Brahmagupta is often credited with providing zero its modern form and meaning. In his seminal text, the Brahmasphutasiddhanta, Brahmagupta established rules for arithmetic operations involving zero, such as addition and subtraction. This marked a significant leap forward in mathematical theory.

Brahmagupta and the Birth of Modern Zero

One of the most important milestones in the history of zero was Brahmagupta’s innovative work. He not only defined zero as a number but also explored its properties within equations. For example, he described zero as the result of subtracting a number from itself. This was a radical departure from earlier placeholder systems, as it gave zero an independent identity within mathematics.

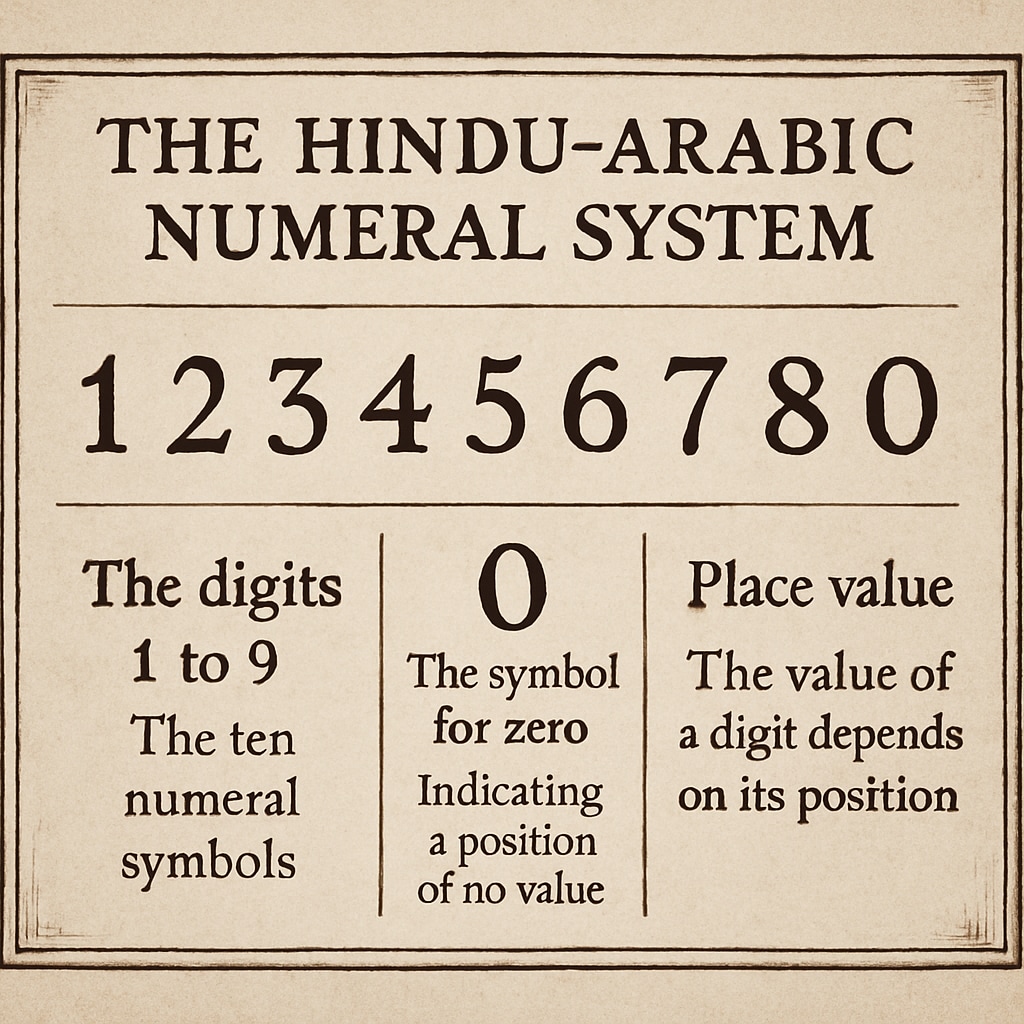

Moreover, the Indian numeral system, including zero, was later transmitted to the Arab world. Prominent scholars like Al-Khwarizmi translated Indian texts, laying the groundwork for the spread of zero to Europe. This exchange of knowledge demonstrates how interconnected ancient civilizations were in advancing mathematical ideas.

The Spread and Global Impact of Zero

Zero’s journey from India to the rest of the world was facilitated by the Islamic Golden Age. During this period, scholars in the Middle East preserved and expanded upon Indian mathematical concepts. Al-Khwarizmi’s works, for instance, introduced the Indian numeral system—including zero—to the Arab world. His texts were later translated into Latin, which brought these ideas to Europe.

By the 12th century, zero had become an integral part of European mathematics. Italian mathematician Fibonacci, in his book Liber Abaci, promoted the use of Arabic numerals, including zero. This shift from Roman numerals to the more versatile Hindu-Arabic system revolutionized trade, science, and engineering.

Zero in Modern Mathematics and Beyond

In the modern era, zero is not only a fundamental part of arithmetic but also integral to advanced mathematical theories. For example, zero is central to calculus, algebra, and computer science. Without zero, concepts such as binary code—the foundation of modern computing—would not exist.

Zero also plays a philosophical role, representing nothingness and the void in various cultural and metaphysical contexts. From the ancient Indian concept of “Shunya” to modern existential philosophy, zero continues to inspire exploration beyond mathematics.

Conclusion: Why Zero Matters

The question “who invented zero” is more than a historical inquiry; it is a window into the evolution of human thought. From its modest beginnings as a placeholder in Mesopotamia to its refinement in India and dissemination across the globe, zero has profoundly shaped mathematics, science, and philosophy. Its invention underscores the collaborative nature of human progress, reminding us that transformative ideas often emerge from the intersection of diverse cultures.

Zero is more than just a number—it is a testament to humanity’s capacity for abstract thinking and innovation. As we continue to explore new frontiers in science and technology, the legacy of zero remains as relevant as ever.

Readability guidance: This article maintains an accessible tone while providing historical and academic insights. Short paragraphs, clear transitions, and strategically placed images enhance readability. External links to reliable sources enrich the content and provide further exploration opportunities.