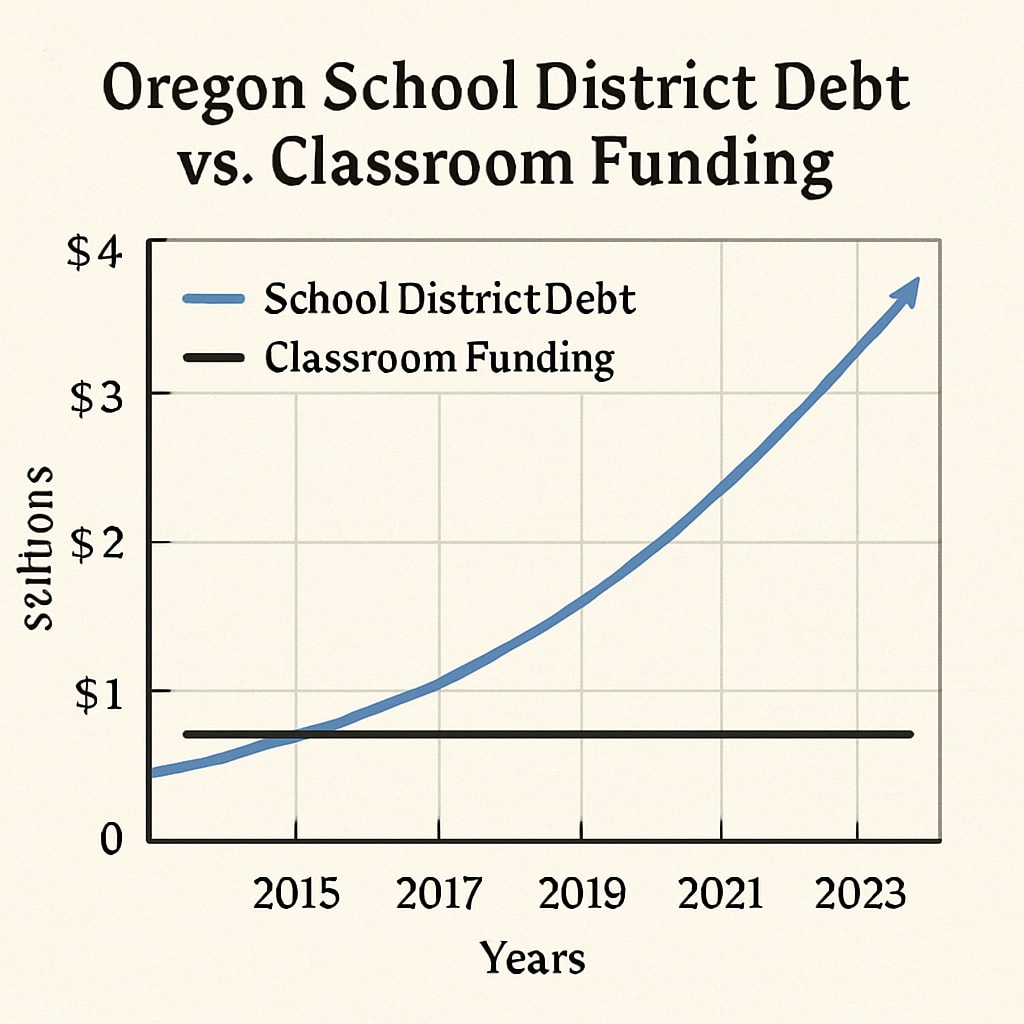

The growing reliance on education bonds, OSCIM grants, and school district debt across states like Oregon reveals a troubling trend in public education financing. As districts face budget shortfalls, state programs increasingly encourage long-term borrowing for infrastructure rather than direct classroom support.

The OSCIM Grant Paradox

Oregon’s School Capital Improvement Matching (OSCIM) program offers districts 50-70% reimbursement for qualified construction projects. While this sounds beneficial, it creates perverse incentives:

- Districts prioritize “shovel-ready” building projects over academic programs

- Matching requirements force districts to take on additional debt

- Funds cannot be reallocated to teacher salaries or instructional materials

According to Oregon Department of Education data, districts have accumulated $2.3 billion in bond debt since OSCIM’s 2015 launch.

Debt vs. Direct Classroom Investment

While facilities matter, the debt-driven approach creates measurable imbalances:

| Resource | Funding Change (2015-2023) |

|---|---|

| Building projects | +47% |

| Teacher positions | -12% |

The Ripple Effects

This financing model creates cascading challenges:

- Debt service consumes larger portions of operating budgets

- Districts face credit rating downgrades, increasing borrowing costs

- Teacher turnover rises as salaries stagnate

A National Center for Education Statistics study shows Oregon’s teacher retention rate dropped 8% since 2018.

Policy alternatives exist: States could revise matching programs to allow hybrid funding models where districts allocate portions to both facilities and instruction. However, such reforms require political will to challenge entrenched construction interests.