The Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA), introduced as an educational experiment in the 1970s, was designed to improve children’s early reading fluency. While the system showed promise in its intended goals, it unintentionally created long-term challenges with standard English spelling for many students who were exposed to it. This article explores the origins of ITA, its teaching principles, and how it left a lasting impact on the literacy skills of those educated under this methodology.

What Was the Initial Teaching Alphabet?

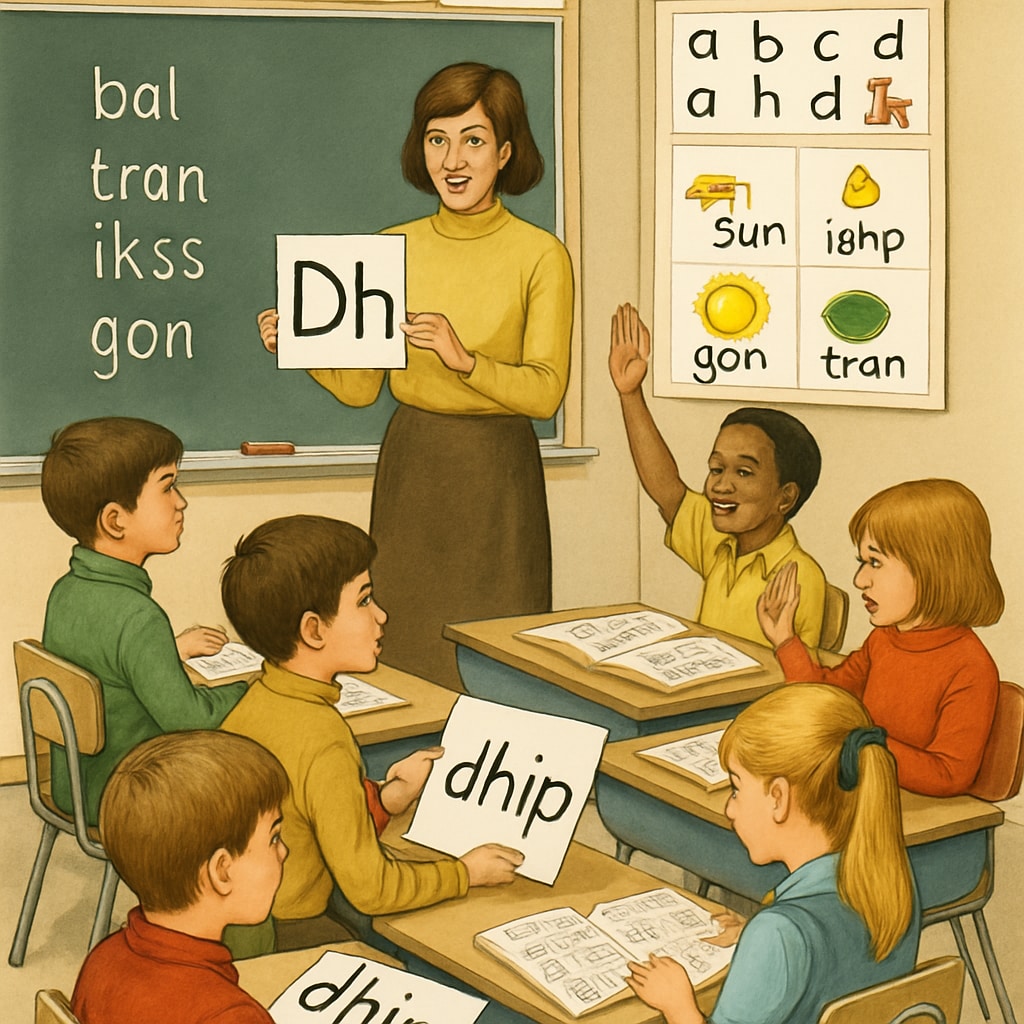

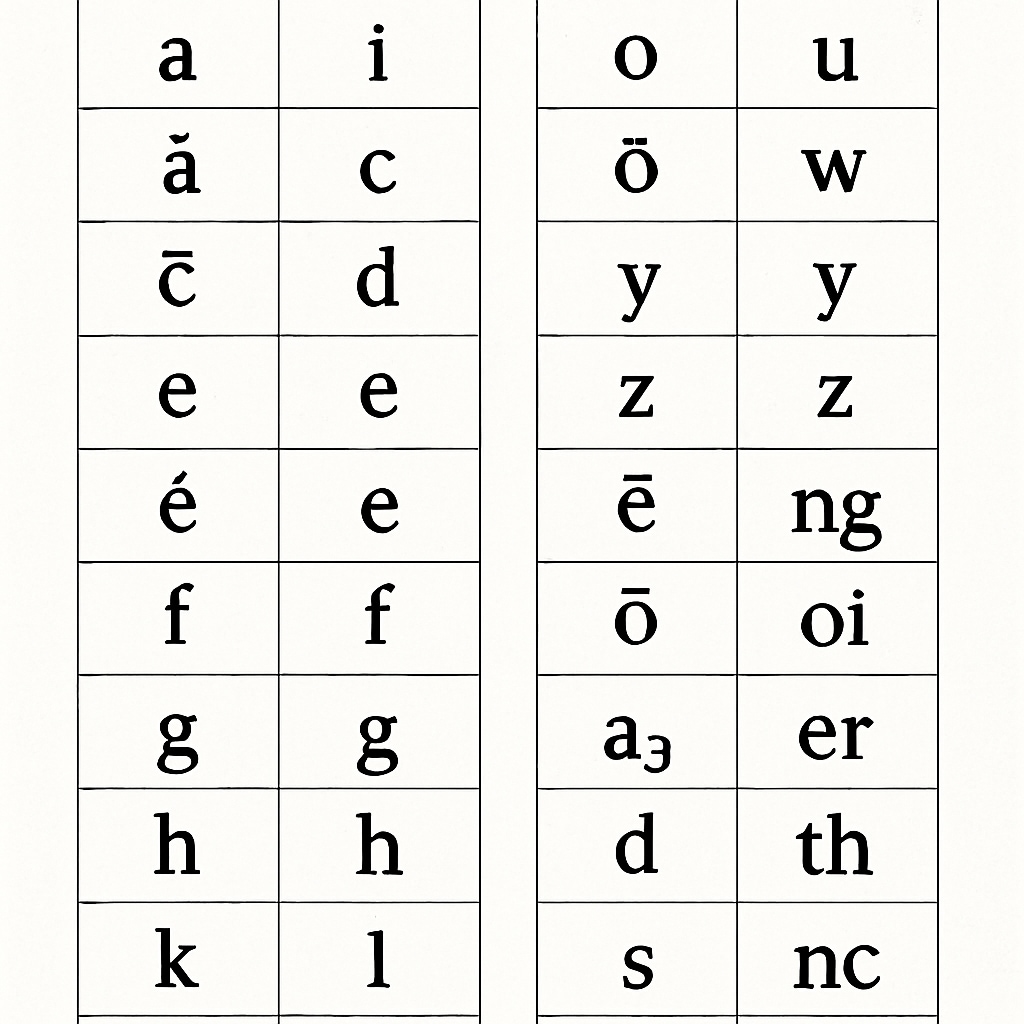

The Initial Teaching Alphabet, also known as ITA, was developed in the 1960s by Sir James Pitman, a British education reformer. This phonetic alphabet was intended to simplify the complexities of English spelling by using a set of 44 characters to represent each distinct sound in the English language. Unlike standard English orthography, which often features irregular spellings, ITA sought to create a one-to-one correspondence between sounds and symbols.

For example, instead of spelling “phonics,” the ITA system might render it as “foniks,” relying on phonetic accuracy rather than historical or etymological conventions. The hope was that this simplified approach would accelerate reading fluency in young children, allowing them to decode words more easily.

During the 1970s, ITA gained traction in the United Kingdom, the United States, and other English-speaking regions. It was implemented in many schools as part of experimental literacy programs. Advocates argued that ITA’s focus on phonetics would provide a strong foundation for later literacy skills. However, the system also came with significant challenges.

Did ITA Improve Early Literacy?

Proponents of the Initial Teaching Alphabet celebrated its early success in improving reading fluency among young learners. Studies conducted during the height of ITA’s popularity suggested that children taught with this system often learned to read faster than their peers who used traditional English orthography.

However, the benefits of ITA were largely short-term. As students transitioned to standard English spelling, many struggled to adapt. The phonetic characters they had become accustomed to did not align with conventional spelling rules, leading to confusion and frustration. In essence, ITA created a “double learning curve” for students: first mastering the phonetic alphabet and then relearning how to spell in standard English.

For example, a child who learned to write “sed” in ITA might later struggle to remember the standard spelling “said.” This misalignment between ITA and traditional English orthography became a significant barrier for many students.

Long-Term Consequences: Spelling Difficulties in Adulthood

While ITA aimed to simplify the learning process, its long-term consequences often included persistent spelling difficulties for adults who were taught using this system. Even decades later, many report challenges in mastering irregular spellings or remembering exceptions to English orthography rules.

Researchers have noted that early exposure to ITA may have disrupted the development of “orthographic mapping”—the brain’s ability to store and recall the visual patterns of correctly spelled words. As a result, individuals educated under ITA often rely more heavily on phonetic spelling strategies, which can lead to errors in written communication.

For example, a former ITA student might spell “enough” as “enuf,” failing to integrate the non-phonetic aspects of traditional English spelling. This issue underscores the potential risks of emphasizing phonetics at the expense of standard orthographic conventions.

Lessons from the 1970s: Balancing Phonics and Orthography

The rise and fall of the Initial Teaching Alphabet offer important lessons for educators and policymakers. While phonics-based approaches can be effective for teaching early reading skills, they must be carefully integrated with standard orthographic instruction to avoid creating long-term challenges.

Modern literacy programs often blend phonics with whole-language approaches, ensuring that students develop both decoding skills and an understanding of standard English spelling patterns. By striking this balance, educators can support early literacy development without compromising long-term spelling proficiency.

Moreover, the experience of ITA highlights the importance of evidence-based interventions in education. Before implementing large-scale changes, it is crucial to consider not only the immediate benefits but also the potential long-term consequences for students.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Initial Teaching Alphabet

The Initial Teaching Alphabet was an ambitious attempt to revolutionize early literacy education in the 1970s. While it succeeded in improving early reading fluency, its unintended impact on spelling proficiency serves as a cautionary tale for educators. The challenges faced by former ITA students underscore the need for a balanced approach to literacy instruction—one that prioritizes both phonics and traditional orthographic conventions.

As we reflect on the legacy of ITA, it reminds us of the complexities of language learning and the importance of thoughtful, research-driven educational practices. By learning from past experiments, we can better design programs that meet the needs of all learners, both in the short term and for the rest of their lives.

Readability guidance: This article uses short paragraphs, clear transitions, and accessible language to ensure readability. Lists and examples are incorporated to clarify key points, and passive voice is minimized to maintain an active tone throughout the text.