The Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA), a phonetic-based teaching method introduced in the 1960s and widely adopted during the 70s, aimed to simplify the learning process for beginning readers. While initially praised for its innovation, this experimental approach caused unexpected challenges, particularly in spelling proficiency. Decades later, researchers and educators have identified its long-term impacts on learners and its implications for language instruction today.

What Was the Initial Teaching Alphabet?

The Initial Teaching Alphabet was developed by Sir James Pitman as a phonetic writing system designed to help children learn to read faster. Unlike traditional English orthography, ITA employed a simplified alphabet consisting of 44 characters, representing distinct phonemes (the smallest units of sound). This system was intended to reduce confusion caused by English spelling irregularities and allow young learners to focus on decoding sounds rather than memorizing inconsistent spelling rules.

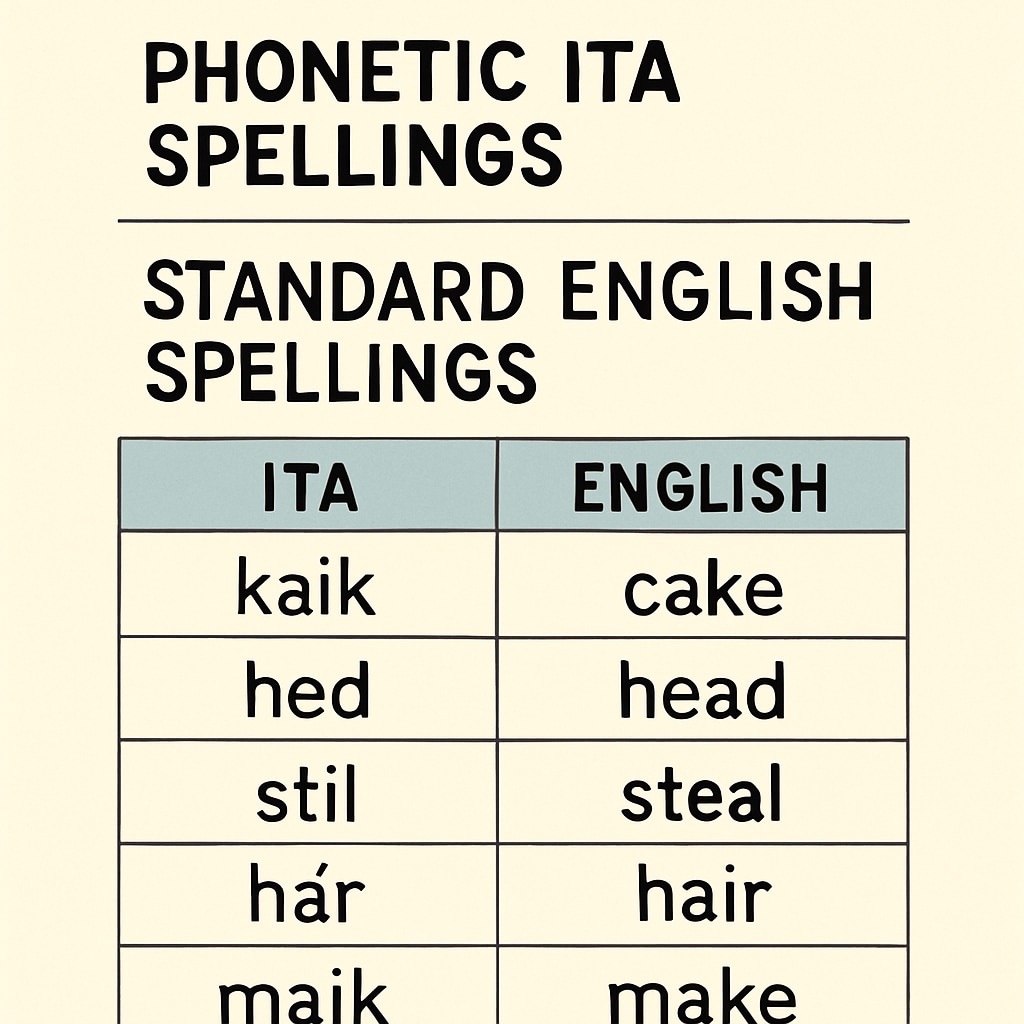

For example, words like “phone” were spelled phonetically as “fohn,” eliminating silent letters and complex spelling patterns. The system gained popularity in the UK and the US during the 1960s and 70s, with schools adopting ITA as a primary instructional method for early literacy education.

The Problems with ITA Implementation

While the Initial Teaching Alphabet seemed promising, its practical application revealed significant flaws. One major issue was the transition from ITA back to standard English orthography. Students who learned to read and write using ITA often struggled to adapt to conventional spelling rules, leading to confusion and persistent spelling errors.

The use of ITA also created a disconnect between phonetic spelling and the traditional English writing system. For example, children accustomed to ITA’s phonetic simplicity found words with silent letters, irregular vowel sounds, or homophones (e.g., “read” and “reed”) more difficult to grasp later in their education. As a result, many developed long-term spelling disabilities that persisted into adulthood.

Furthermore, critics argued that ITA neglected the broader linguistic and cognitive processes involved in language acquisition. Reading and writing are not solely about phonetic decoding; they also require an understanding of morphology (word structure), syntax (sentence structure), and semantics (meaning). ITA’s narrow focus ignored these complex aspects of literacy development.

Long-term Effects on Spelling Skills

Studies conducted in the years after ITA’s decline highlighted its unintended consequences. Learners who were taught using ITA often displayed spelling errors rooted in phonetic approximations, such as writing “wuz” instead of “was” or “thur” instead of “there.” These habits proved difficult to overcome, even with additional instruction in standard English orthography.

In addition, ITA students frequently showed delayed mastery of word recognition skills, as their early exposure emphasized sound-based decoding at the expense of visual recognition of standard spellings. This contributed to difficulties in reading fluency and comprehension, especially when encountering complex or unfamiliar vocabulary.

As a result, the educational community largely abandoned ITA by the late 1970s. However, its legacy serves as a cautionary tale regarding the risks of overly simplified teaching methods that neglect the intricacies of language learning.

Lessons for Modern Language Teaching

The rise and fall of the Initial Teaching Alphabet offer valuable insights for today’s educators. First, it underscores the importance of balancing phonetic instruction with exposure to standard spelling conventions. While phonics remains a crucial component of early literacy education, it should be complemented by strategies that address irregularities in English orthography.

Second, the ITA experiment highlights the need for a comprehensive approach to language learning. Effective literacy instruction should integrate phonics, morphology, syntax, and semantics to ensure students develop well-rounded reading and writing skills. For example:

- Phonics-based decoding techniques can be paired with visual recognition exercises to reinforce standard spelling patterns.

- Teaching methods should introduce context-based reading tasks to improve comprehension and vocabulary acquisition.

- Multisensory approaches, such as combining auditory, visual, and tactile experiences, can aid diverse learners in mastering complex language concepts.

Finally, the ITA experiment serves as a reminder of the potential consequences of educational innovations. While new methods may offer exciting possibilities, they must be rigorously tested and evaluated to ensure they address the full scope of learners’ needs and avoid unintended drawbacks.

In conclusion, the Initial Teaching Alphabet was a bold attempt to revolutionize early literacy instruction, but its long-term impacts on spelling skills highlight the dangers of oversimplification in language teaching. Educators today can learn from this historical experiment to create more effective and balanced approaches to literacy education.