The Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA), introduced during the 1970s, aimed to revolutionize literacy education. Designed as a simplified phonetic alphabet, ITA sought to ease the journey of young learners into reading and writing. However, while the method gained initial popularity, it ultimately led to unforeseen challenges, particularly in spelling development, that persist for some learners even today. This article explores the history of ITA, its implementation, and the long-term effects on spelling ability, offering valuable insights for modern education.

The Origins and Goals of the Initial Teaching Alphabet

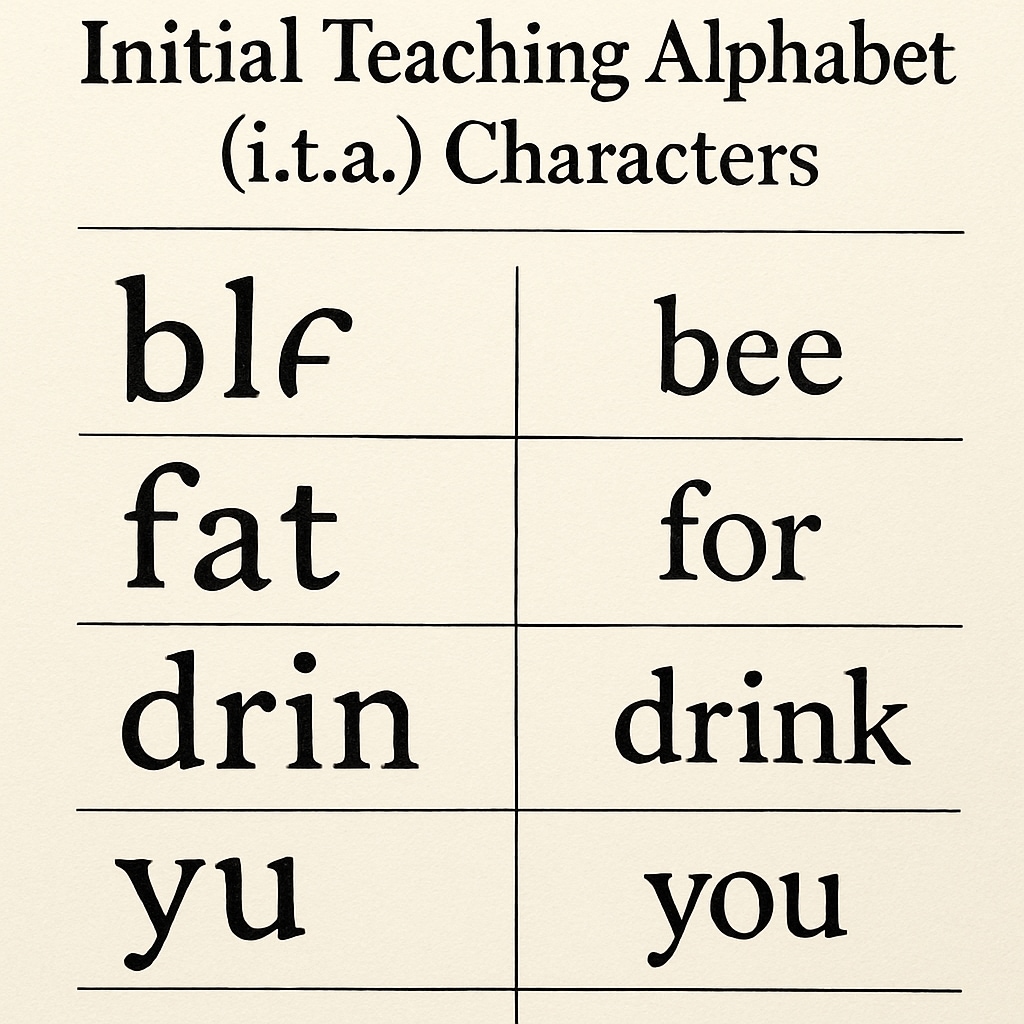

In the mid-20th century, literacy was a growing concern in English-speaking countries. Educators sought innovative ways to simplify the complex and often inconsistent rules of English spelling. ITA was developed by Sir James Pitman, a British educator, as a response to these challenges. The system introduced 44 characters that corresponded to the phonemes (distinct sounds) of spoken English, replacing the traditional 26-letter alphabet. For example, “sh” was represented by a single unique symbol, and “ee” had its dedicated character.

The primary goal of ITA was to eliminate the confusion caused by irregular spelling patterns, making it easier for young children to decode words phonetically. Supporters believed that by focusing on phonemic awareness, children could more quickly grasp the mechanics of reading and writing, later transitioning to standard English orthography.

Challenges in Implementation and Transition

Despite its optimistic beginnings, ITA faced significant hurdles during implementation. While children initially showed rapid progress in reading and writing, transitioning from ITA to standard English spelling proved problematic. The reliance on phonetic symbols created confusion when students were introduced to conventional spelling rules. For example, a child accustomed to writing “sed” for “said” might struggle to adjust to the irregular spelling of the standard alphabet.

Another issue was the inconsistency in how ITA was taught. Some schools implemented it as a standalone system, while others used it alongside traditional spelling instruction. This lack of uniformity compounded the difficulties faced by learners, particularly in later years. Additionally, parents unfamiliar with ITA often found it challenging to support their children’s learning at home.

Long-Term Effects on Spelling Ability

One of the most significant criticisms of ITA is its long-term impact on spelling proficiency. Research indicates that many students who learned through ITA developed persistent spelling difficulties, even into adulthood. These challenges stem from the disconnect between ITA’s phonetic approach and the irregularities of standard English spelling. Learners often retained ITA-influenced spellings, leading to errors such as “sed” for “said” or “frend” for “friend.” This phenomenon, known as “orthographic interference,” highlights the risks of deviating too far from standard orthographic conventions during early education.

Lessons for Modern Education

The experience of ITA offers several lessons for contemporary educators. While innovation in teaching methods is essential, it must be balanced with careful consideration of long-term implications. ITA’s failure to account for the complexity of transitioning to standard spelling underscores the importance of aligning instructional methods with the ultimate goals of literacy education.

Today, educators emphasize the importance of phonics-based instruction alongside exposure to standard spelling conventions. Programs like synthetic phonics, which teach children to decode words by blending sounds, have proven more effective in balancing phonemic awareness with spelling accuracy. Furthermore, the integration of technology in literacy education provides new opportunities to engage learners while reinforcing standard orthographic rules.

As we reflect on the legacy of ITA, it serves as a reminder that educational experiments, while well-intentioned, must be rigorously evaluated for their long-term effects. The goal of literacy education should not only be to simplify the learning process but also to ensure that learners are equipped with the skills they need for lifelong success.

Readability guidance: This article uses short paragraphs, clear subheadings, and examples to enhance readability. Lists and images are incorporated to summarize key points and maintain reader engagement. Transitions such as “however,” “therefore,” and “in addition” are used throughout to ensure smooth flow between ideas.