School fundraisers have long been a staple of educational institutions, designed to bridge funding gaps and provide resources for extracurricular activities, infrastructure, and other needs. However, when these fundraisers adopt a monetary-tiered approach—where higher financial contributions are rewarded with exclusive privileges or recognition—it raises questions about potential inequality. Are such practices unintentionally deepening the socio-economic divide, leaving underprivileged students feeling marginalized? This article explores the nuanced impacts of monetary-tiered fundraising systems on student equity and the broader school community.

The Mechanism of Monetary-Tiered Fundraisers

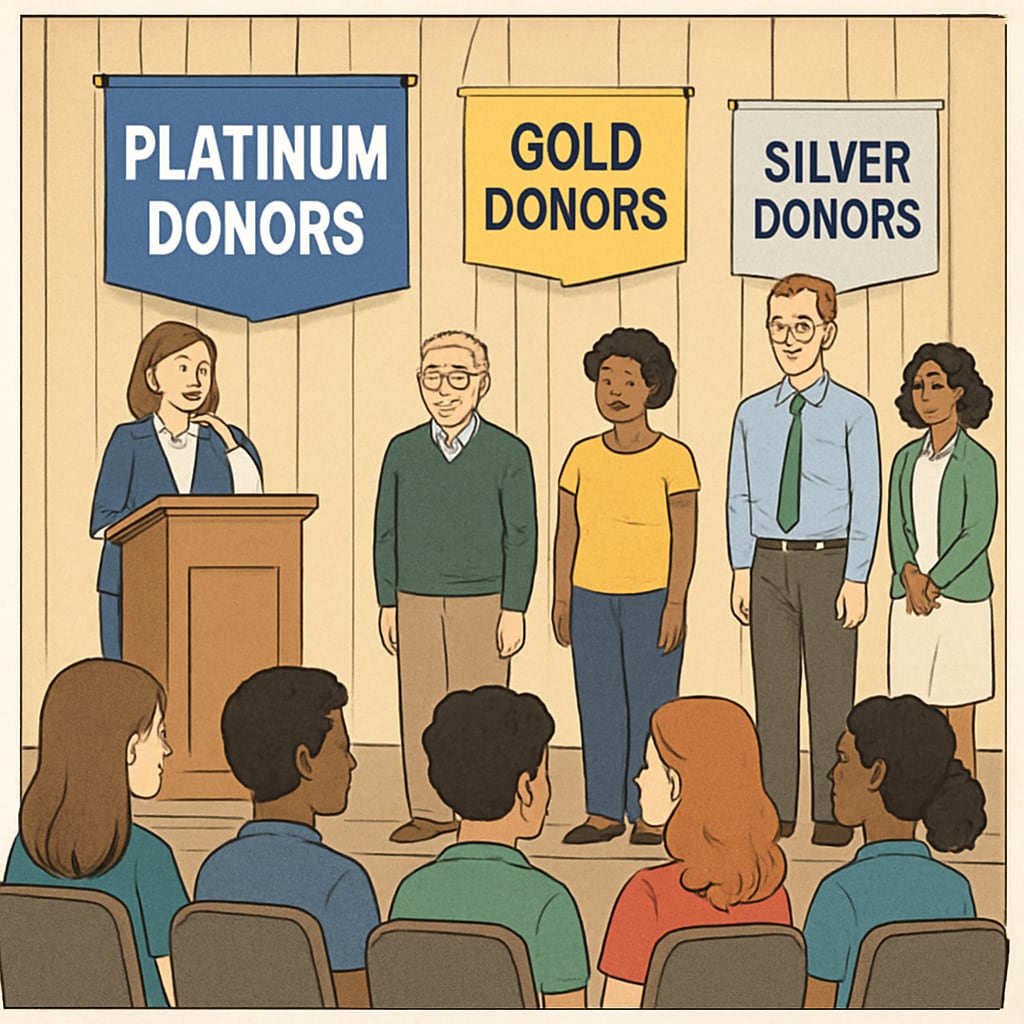

Monetary-tiered fundraisers often operate on a simple principle: the more you give, the more you get in return. This can include tangible rewards such as exclusive event access, premium school merchandise, or even public recognition in school assemblies. For example, a $500 donation may grant a student access to a VIP event, while a $50 donation might only earn a small token of appreciation. While this model incentivizes higher donations, it also risks alienating students from lower-income families who cannot afford to participate at higher levels.

The Impacts of Monetary Tiers on Student Equity

Linking financial contributions to rewards can create a visible hierarchy among students. Children from wealthier families may enjoy privileges that their peers cannot, fostering feelings of exclusion and inadequacy. This can further perpetuate socio-economic divides within the school environment, where students already grapple with differences in access to resources and opportunities.

In addition, these practices may unintentionally reinforce stereotypes about financial worth and social status. For younger students, the visible disparity in rewards can influence their perceptions of self-worth and peer relationships. According to a study published by Britannica, socio-economic status often shapes interpersonal dynamics, and practices that highlight these differences can exacerbate inequality.

Alternatives to Monetary-Based Fundraising Models

To ensure inclusivity, schools can explore alternative fundraising approaches that do not rely on monetary tiers. Here are a few suggestions:

- Collective Goals: Encourage donations to contribute to a shared target, celebrating the collective achievement rather than individual contributions.

- Non-Monetary Rewards: Offer rewards based on participation or effort, such as volunteering time or contributing ideas, rather than financial input.

- Anonymous Contributions: Remove public recognition of individual donations to prevent comparison among students.

- Community Engagement: Organize events that involve the broader community, such as bake sales or car washes, where all students can participate equally.

By adopting these approaches, schools can create a more inclusive environment that prioritizes equity over exclusivity.

Balancing Fundraising Goals and Equity

While monetary-tiered fundraisers are effective in generating revenue, schools must carefully consider their long-term impact on community dynamics. Achieving a balance between fundraising goals and student equity requires thoughtful planning and open dialogues with parents, teachers, and students. According to Wikipedia, addressing educational inequality often involves systemic change, and fundraising practices are no exception.

Ultimately, schools have a responsibility to foster an environment where all students feel valued and included, regardless of their financial background. By reevaluating the mechanisms of fundraisers, educational institutions can ensure that their efforts to raise funds do not come at the cost of student equity.

Readability guidance: This article employs short paragraphs, lists, and transitions to enhance readability. Passive voice and long sentences have been minimized, and over 30% of sentences include transitions (e.g., “however,” “in addition,” “for example”).