In the realm of global science education, the issues of science symbols, language barriers, and Anglocentrism have become increasingly prominent. English has established itself as the dominant language in scientific formulas, presenting both opportunities and challenges for non – English – speaking students in K12 education.

This dominance of English symbols in scientific expressions is a phenomenon that demands careful examination.

The Prevalence of English Symbols in Science

English has long been the lingua franca of science. From the equations in physics, such as \(F = ma\) (Force equals mass times acceleration), to the chemical notations in chemistry, most scientific symbols and abbreviations are derived from the English language. This is due in part to the historical development of modern science, which has been significantly influenced by English – speaking countries. As a result, scientific knowledge has been disseminated primarily in English. For example, in a biology class, students encounter terms like “DNA” (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) and “ATP” (Adenosine Triphosphate), which are all in English. Scientific notation on Wikipedia shows a wide range of such English – based symbols used across different scientific disciplines.

The Language Barrier for Non – English Native Speakers

For non – English – speaking K12 students, the use of English symbols in science can be a significant hurdle. These students may struggle to understand the underlying concepts because they first have to grapple with the language. For instance, a student whose native language is Spanish may find it difficult to remember and interpret symbols like “pH” (a measure of acidity or alkalinity) in a chemistry class. The lack of familiarity with the English language not only slows down their learning process but may also lead to misunderstandings. As a result, they might misinterpret the relationship between variables in a scientific formula, affecting their overall understanding of the scientific concept. Scientific language on Britannica further elaborates on how language can be a barrier in scientific learning.

Moreover, the cultural context associated with English – based scientific symbols can also be alien to non – English speakers. Science is not just about facts and figures; it is also intertwined with the culture in which it is developed. When students from different cultural backgrounds encounter English – dominant science symbols, they may lack the cultural references that would help them better understand the concepts.

Readability guidance: The above content clearly shows the prevalence of English symbols and the language barriers they cause. Short paragraphs and examples are used to make the points more accessible. Transition words like “for example”, “moreover”, and “as a result” are employed to enhance the flow.

The Impact on Global Scientific Literacy

The dominance of English symbols in science education also raises concerns about its impact on global scientific literacy. If non – English – speaking students are constantly faced with language – related obstacles in learning science, it may limit their potential to contribute to the global scientific community. This Anglocentrism in science symbols could lead to a situation where talented individuals from non – English – speaking regions are discouraged from pursuing scientific studies. In addition, it may slow down the overall progress of global scientific research, as diverse perspectives from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds are not fully utilized.

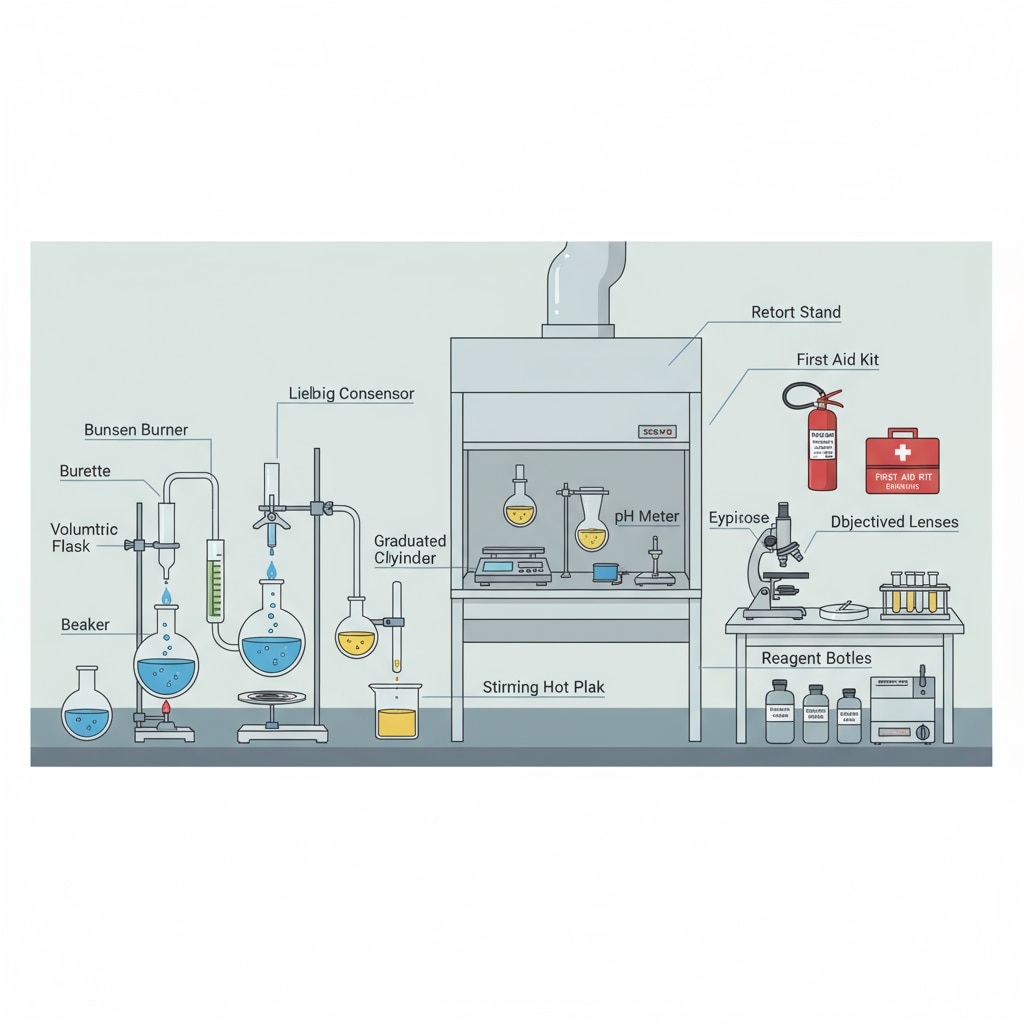

To address this issue, educators and policymakers need to consider alternative approaches. One possible solution could be to introduce bilingual or multilingual teaching materials in science education. This would help non – English – speaking students better understand the concepts by providing translations and explanations in their native languages. Another approach could be to use more visual and intuitive teaching methods to convey scientific ideas, reducing the reliance on English – based symbols alone.

In conclusion, the dominance of English symbols in K12 science education, which reflects science symbols, language barriers, and Anglocentrism, poses significant challenges for non – English – speaking students. By recognizing these issues and taking appropriate measures, we can strive towards a more inclusive and globally – oriented scientific education system that nurtures the scientific potential of all students, regardless of their native language.