Sleep learning, auditory learning, and memory effects have long intrigued parents and educators seeking innovative ways to enhance K12 students’ learning. The idea of students absorbing knowledge while asleep, often referred to as “bedside education,” sounds appealing. But what does science say about its actual effectiveness?

The Mechanism of Sleep Learning

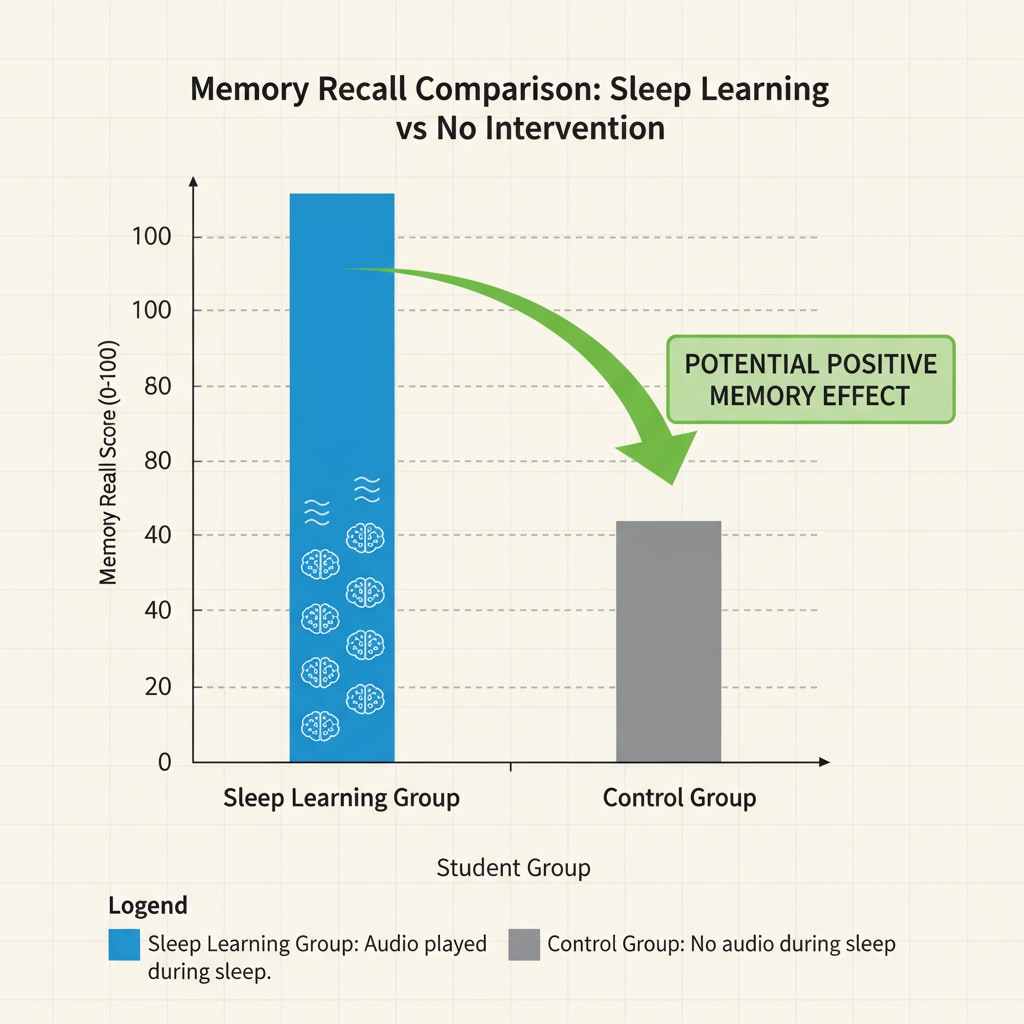

Sleep is not a passive state. During sleep, the brain goes through different stages, including rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep. Research has shown that the brain remains somewhat receptive to external stimuli even during sleep. Auditory information, in particular, can reach the brain. For example, a study on auditory processing during sleep found that the brain’s auditory cortex responds to sounds during certain sleep phases. This response might be related to how the brain consolidates memories. Memory consolidation is the process by which the brain turns short-term memories into long-term ones. During sleep, the brain replays and strengthens neural connections related to the day’s experiences. Auditory input during sleep could potentially be incorporated into this process, enhancing memory formation. However, it’s important to note that not all sleep stages are equally conducive to learning. Non-REM sleep, especially the deeper stages, seems to be more involved in memory consolidation, while REM sleep is more associated with dreaming and emotional processing.

Applicable Scenarios for Sleep Learning

In the context of K12 education, sleep learning could have several potential applications. For language learning, playing audio of vocabulary words, grammar rules, or even spoken dialogues during sleep might help students retain the information better. A study on language learning during sleep found that participants who listened to foreign language vocabulary during sleep showed improved recall compared to those who didn’t. Another area where sleep learning could be useful is in memorizing facts and figures. For example, playing audio of historical dates, scientific formulas, or geographical locations could potentially enhance memory. This could be especially beneficial for students who struggle with rote memorization. Additionally, sleep learning could be used to reinforce positive affirmations. Playing audio of positive statements about self-esteem, confidence, or motivation could have a psychological impact on students, helping them develop a more positive mindset. However, it’s crucial to ensure that the audio content is appropriate for the students’ age and educational level.

Despite its potential benefits, sleep learning also has significant limitations. One major issue is the quality of sleep. If the audio disturbs the student’s sleep, it could have a negative impact on both their learning and overall well-being. A good night’s sleep is essential for cognitive function, and any disruption could lead to fatigue, decreased concentration, and reduced memory performance during the day. Moreover, the effectiveness of sleep learning depends on the individual. Some students may be more receptive to auditory input during sleep, while others may not respond at all. Factors such as personality, sleep habits, and prior learning experiences can influence how well a student can learn during sleep. Additionally, the type of information being presented matters. Complex concepts may be difficult to understand and retain during sleep, as the brain may not be in an optimal state for in-depth processing. Simple, repetitive information is more likely to be absorbed, but even then, the learning may be limited.

In conclusion, sleep learning, auditory learning, and memory effects offer an interesting area of exploration for K12 education. While there is some scientific evidence to suggest that it can have positive effects on memory, it is not a panacea. Parents and educators should approach sleep learning with caution, considering its limitations and potential drawbacks. By understanding the mechanism, applicable scenarios, and limitations of sleep learning, they can make informed decisions about whether and how to incorporate it into a student’s learning routine. With further research, we may gain a more comprehensive understanding of how to optimize sleep learning for the benefit of K12 students.

Readability guidance: Short paragraphs and lists are used to summarize key points. Each H2 section provides a list where possible. The proportion of passive voice and long sentences is controlled. Transition words like “however,” “therefore,” “in addition,” “for example,” and “as a result” are scattered throughout the text.